Do you know what your body is capable of on any given day? And more importantly, do you know what you CAN’T do?

It’s a difficult concept to grasp. Here’s what it takes:

Pushing yourself to your limits in races and workouts – over and over again.

Decades of consistent training.

Learning why you get injured (sometimes the hard way) and how to run the extremely fine line between staying injury-free and hard training.

Running personal bests in race distances on the track, cross country, and road (and understanding the differences between all three).

For new runners, you’ll have no idea what you can and can’t do. This is normal!

When I started running, I couldn’t even finish an easy 3 miler. And I was this sore for a week.

But after years of consistency, you’ll understand the nuances between pain, soreness, “normal” tired vs. “over-trained” tired, and when to dial back your training because of injury risk.

It’s a slow process, but the result is worth the time: you’ll know exactly when to push and when to rest.

After nearly two decades of training, I think I have most of this figured out for myself.

So it was with a heavy heart that I made the right decision last Saturday: I dropped out of my first ultramarathon, the Dirty 30 50km.

I knew I couldn’t continue running without getting a severe injury. So I made one of the hardest decisions of my life. I quit.

The Dirty 30 50km Race Report

The race started perfectly. My intention was to keep the effort the same as all my other long runs in the mountains – and it worked beautifully.

I stayed comfortable on the flats and downhills, but appropriately challenged on the early hills.

I had run up to 20 miles on some of these same trails, averaging anywhere from 7:55 – 8:10 per mile. So I was confident I could run the first 20 miles in 2:45 (8:15 pace) and still feel good.

The terrain had other plans.

Three ridiculous miles (13, 16, and 17) were so rocky, steep, and meandering that I got lost a few times and came to a complete stop, looking around for where to go. That threw off my pace considerably.

Take a look at my mile splits:

7:52

7:27

10:27

11:42

6:54

8:48

9:31

10:09

8:17

7:13

9:09

7:13

13:20

8:24

8:30

14:12

11:23

I ended up running about 17.5 miles in 2:45 – after getting lost three times and wandering around a mountain top.

But before the injury and getting lost, I had a blast. Some highlights:

- Breathtaking views of Mt. Evans, Aspen tree-lined meadows, and mountain streams

- Perfect weather – sunny, crisp mountain air, and plenty of shade under the cover of pine trees

- Running with a few big name ultrarunners, including Timothy Olsen

The group I ran with for most of the way was great (a few hikers called us “gazelles” as we ran by) and I got a fun lesson in how to descend rocky single-track when they put a minute on me every downhill…

Until my IT band started to hurt (and before I got lost), I was averaging under 9:00 pace per mile and feeling great.

It wasn’t hard. I wasn’t sore. I was in a good mental state and fueling was going according to plan.

I was confident I could maintain a similar pace, which with a few more walk breaks, would have put me in the top 10 (!). I’m probably being a little optimistic, but it’s still encouraging.

You can see the full results here.

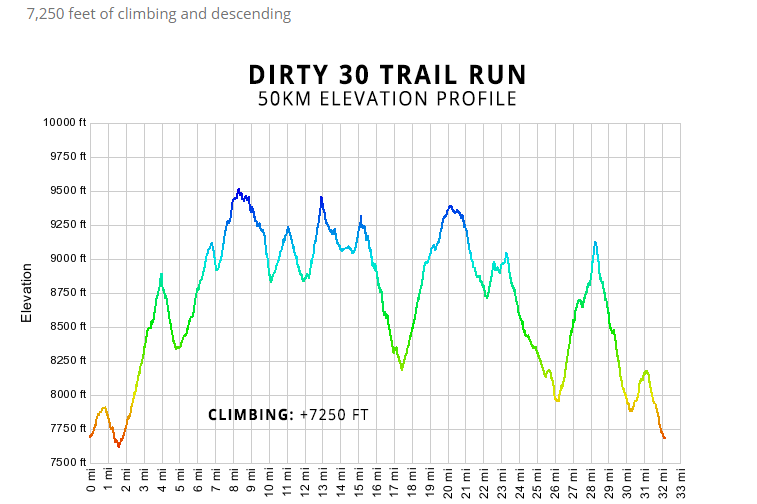

What’s frustrating is that my race was dictated not by my fitness, but by my structural ability to withstand the unreal elevation changes and trail technicality.

After miles of rocky descent, my IT band simply failed. Or more specifically, my left hip and glute medius failed, causing pain associated with ITBS.

This is my weak link. The Kryptonite that causes a mechanical break-down in my form when elevation and terrain proves too much to handle.

Despite the injury, I had a lot of fun. I’ve been reflecting on this race for a few days now, trying to understand the skill set of a good mountain ultra runner.

I think I have a few good ideas for you:

What does it take to be a good ultra runner?

The view from near the 10-mile mark at the Dirty 30 50k

If you want to be a competitive mountain ultra runner, you need two primary abilities:

- The ability to cover crazy terrain in 10-14 minutes per mile – but then be able to rapidly accelerate on flat or downhill sections to 6:00 – 7:00 per mile.

- The structural ability to withstand the terrain, distance, and pace changes of mountainous ultras (this is where I failed).

That’s about it.

Of course, there are MANY components to each ability. To run anywhere from 6:00 – 14:00 / mile for 4+ hours over ridiculous trails requires an enormous aerobic engine. So priority #1 must be to train your endurance.

You must also:

- Run hills competently (even when you’re tired)

- Navigate technical trails with confidence (learn more about trail running here)

- Be comfortable changing pace based on the terrain, elevation, and altitude

To improve your structural fitness (the ability of your muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bones to withstand the impact of running), you have to do two things:

Run a lot (no better way to condition your body for running!).

Get really, really strong (here’s how to get started: strength work and progression).

Many traditional ultra running training programs will focus exclusively on running. It’s the absolute primary focus, but it’s not the only component to success.

And approaches like CrossFit Endurance will focus on the strength aspect of training – even though it’s not the primary activity (so much for specificity of training…).

The best approach? As usual, it’s neither extreme. It’s a blend of the two: a focus on endurance and high mileage but one that also includes a good amount of strength exercises. This approaches helps build your structural ability in a different way than simply running a lot.

Both accomplish the same goal, but do so through different mechanisms. At the end of the day, you’re getting even stronger by including both in your training.

Why limit your fitness and performance by skipping strength work or high mileage?

But beyond your abilities, there’s a certain amount of luck. You need great running form and biomechanics – and much of this is genetic. It also takes years to develop and it helps when you start running in your teenage years.

Your particular inefficiencies are magnified when you run fast or run long. And in the case of ultras, any biomechanical problem will be exacerbated after 4, 5, or 6 hours of running trails.

This is why I injured my IT band. My specific anatomy predisposes me to the injury and after nearly three hours of technical trail running on steep mountain grades, I couldn’t continue.

Can you blame my IT band, though? Just look at this elevation profile!

The best ultrarunners are very efficient. They have great form and don’t break down as quickly.

Ultra Training, Gear, and More Details

If you’re curious about the specifics of my race and training, I put together a brief outline of how I prepared, the equipment I used, and fueling.

Ultra Training

My preparation for this race admittedly didn’t go to plan. I experienced a lot of minor aches and pains that prevented me from training more consistently than I would’ve liked.

After trying five different pairs of trail running shoes, I still couldn’t find one that I liked – and each one gave me some type of foot problem (Achilles pain, minor tendinitis on the top of my foot from excessive rubbing, cramped tendons near my ankle).

Plus, my family vacation in March, travel in April, and a conference in May didn’t help my consistency. I thrive on a schedule and routine and prefer to exclusively focus on running in the months leading up to a big race.

This is getting increasingly more difficult as I get older with more responsibilities.

The quality workouts I did do were encouraging:

- Back-to-back long run days (first day on trails, second one on flats with a fast finish)

- Long runs in the mountains

- Medium-long runs up to 15 miles in the mountains during the week

Weekly mileage was unimpressive in the 60-70mi range because of the lack of consistency (before Boston 2014, I ran up to 90 miles per week).

I did a lot of strength work before the ultra, though, including these staples:

- Standard Core Routine (2-3 sets, 2-3 times per week)

- ITB Rehab Routine (2-3 times per week)

- Weights / medicine ball work (1-2 times per week)

Weekly workouts consisted of fartleks, tempo workouts, steady-state runs, and regular strides. It wasn’t ideal, but it’s what I managed.

For specific questions I had about ultra running, I referred to Doug Hay’s Discover Your Ultramarathon program and Bryon Powell’s Relentless Forward Progress.

Equipment & Gear

I’m not a big gear junkie. I only relied on a few pieces of gear during the race:

- Hydration: handheld Amphipod Hydraform bottle

- New Balance Fresh Foam Boracay running shoes

- Nike running shorts

- Boston Marathon technical t-shirt

- Vaseline (I learned my lesson after my nipples bled in my last trail race!)

You’ll notice that my NB running shoes aren’t even trail shoes. I tried FIVE pairs in the months leading up to the race and disliked all of them.

They were stiff, bulky, unresponsive, and hurt my feet. So I went with a road shoe, which worked well on the rocky sections of trail.

Fueling & Nutrition

My fueling plan was simple and one that I knew would work because I practiced it during training.

I relied exclusively on HoneyStinger gels during the race, though I would have started eating banana at the third Aid Station if I hadn’t dropped out.

After mile 5, I drank water with Nuun electrolyte tablets (Strawberry Lemonade is delicious).

My plan was to also listen to my cravings after mile 25. If I waned M&M’s or pretzels, I’d eat them. Alas, I didn’t get that far.

Thank You

A lot of you have sent me notes of encouragement over the last week and I want to thank all of you for that. It means a lot to me.

I appreciate you taking the time to read this, hopefully learn a thing or two, and for actually caring about my running. The SR community always surprises me for the level of support that you freely give to all of us.

I’m not sure what’s next for me. But whatever happens, I’ll make sure to have fun!

– Jason.