A few years into my running career, I noticed a consistent pattern: every year had the same training rhythm. I later learned about periodization – and how helpful it is for runners.

Cyclical training progresses over time

About 15 years ago, when my obsession with training theory, coaching, and exercise science was in full bloom, I recognized that every year followed a similar pattern:

- Summer was reserved for base training (building mileage and the long run without too much speed work)

- That led into cross country in the fall, climaxing in November

- A period of rest and easy running followed

- January – May was the track season, with a small break sometime in March

- After a short break in May or early June, the cycle repeated itself

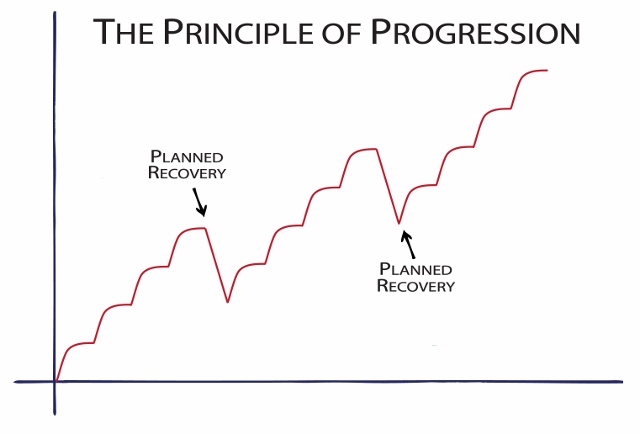

That cycle demonstrates periodization – the ebb and flow of hard work that helps runners reach their potential.

And as a college athlete, we were inserted into a schedule that lent itself to being periodized with cross country in the fall, indoor track in the winter, outdoor track in the spring, and base training in the summer.

After a few years, I started intuitively understanding the concept of periodization and learned a lot of valuable lessons:

- A big base phase in the summer was required for a successful cross country season

- The workouts in July look very different from the workouts in February (or October)

- Total volume and long run distance changed throughout the year based on the season

The term “periodization” first entered my brain when I started reading books about running. And even more descriptive words like mesocycle, macrocycle, and session became ingrained in my vocabulary after getting my USATF coaching education.

But not all of us need advanced training in coaching theory to grasp these concepts.

So in this post, you’ll learn the fundamentals of periodization and how to better apply it to your own running.

What is Periodization?

First, what exactly is periodization?

Periodization is planning. The goal is to give you the best possible chance of peak performance at a certain time.

To accomplish this goal, training is varied and organized over time by manipulating several variables:

- Volume of total running

- Frequency of running (the number of runs per week)

- Intensity (the overall difficulty of training)

- Specificity of workouts to the goal race

- Recovery and rest

One of my favorite running books, Run Faster by Brad Hudson, defines it as:

The term ‘periodization’ refers to how one’s training evolves from the beginning to the end of a training cycle.

Periodization is considered linear when each period or phase of training is very different from the other periods in terms of the degree to which each training type is emphasized or deemphasized.

Periodization is nonlinear when all of the training types are mixed together throughout the training cycle annd changes in emphasis are less extreme.

Steve Magness, in his book Science of Running, has a similar definition:

Periodization is the process of dividing the training into smaller periods of training where the emphasis, or the target, of the training is altered during each period.

Generally a manipulation of the volume, intensity, and frequency of workouts is done to bring a person to peak performance.

USA Track and Field, the governing body of the sport of track & field and road racing, defines it in its coaching curriculum:

Periodization is defined as the process of planning training in oder to produce high levels of performance at designated times.

It’s important to remember that periodization is not an exact plan. There are numerous theories, models, and ideas within the general framework of periodization (more on this later).

Periodization Training Terminology

One of the most impactful benefits of getting my USATF coaching certification is the vocabulary. Formal instruction on organized running clearly defines types of workouts, energy systems, fundamental terms and concepts, training theory, biomechanics, and a lot more.

Let’s review the basic terms used when breaking down periodization:

The Macrocycle

This is a large segment of training that typically is defined as the “season.” It includes one peaking period and a group of or a single major race.

For example, a 20-week marathon training season is a macrocycle.

The Mesocycle

A mesocycle is a smaller segment of the macrocycle typically consisting of a 4-6 week block of training. Each mesocycle usually focuses more on a different physical skill.

For example, the base phase of training during the early part of a macrocycle is a mesocycle.

The Microcycle

Now we’re getting even more granular. A microcycle is a short segment of training that might be a few days long to 1-2 weeks.

A recovery week that’s included in a training plan is a specific microcycle designed to foster both physical and mental recovery.

The Session

A session is an individual training day, occurrence, or practice. In college, I went to practice every day. That practice is an example of a single training session.

These are the fundamental building blocks of a runner’s training cycle. Each term is somewhat subjective and can vary based on the program or coach discussing it.

You’ll see some of these concepts at play in our Season Planner worksheet.

Of course, we can get even more specific and talk about the annual cycle (which might consistent of two macrocycles) or a unit (a section of one session – like a warm-up routine, cool-down run, or strength workout).

I’m not going to dive into the weeds on these definitions. Let’s get the basic framework right and move on!

Different Models of Periodization

Most runners familiar with the term periodization are familiar with linear or classic periodization. It was popularized by Arthur Lydiard in the middle of the last century:

Periodisation comprises emphasizing different aspects of training in successive phases as an athlete approaches an intended target race.

After the base training phase, Lydiard advocated four to six weeks of strength work. This included hill running and springing. This improved running economy under maximal anaerobic conditions without the strain on the achilles tendon, as it was still done in running shoes.

Only after this spikes were put on and a maximum of four weeks of anaerobic training followed.

Then followed a co-ordination phase of six weeks in which anaerobic work and volume taper off and the athlete races each week, learning from each race to fine-tune himself or herself for the target race.

Over the last 10-20 years, a new model has emerged: nonlinear periodization. Popularized by coaches like Renato Canova and Brad Hudson, it’s also called mixed training or a “funnel to specificity” model.

Hudson describes his mixed periodization model in Run Faster:

My training plans feature a more even balance of training types throughout the training cycle. My runners always work on every aspect of running fitness. The distribution of emphasis does change, but I do not reduce any training to merely ‘lip-service’ level, or phase it out entirely, as others do.

In addition to preventing weak links from developing, another advantage of nonlinear periodization is that it increases the adaptability of your training. When you keep all aspects of your running fitness at a fairly high level, you can take your training in any of a number of different directions fairly quickly based on what you seem to need.

When you’ve recently neglected any specific type of training, it’s always necessary to ease into doing more of it – otherwise you risk becoming overtrained or injured.

Both models have been used very successfully throughout the last 60 years.

While I don’t think one is necessarily better than the other, I prefer nonlinear periodization as it’s more flexible and doesn’t isolate each training variable quite so dramatically.

Plus, consistent fast running helps protect you from injury. That’s because your body is always adapted to these stresses so they’re not a shock.

You’ll see in my training programs that strength work, long runs, and strides are present throughout a plan. Workouts in my plans are periodized a bit more linearly, so a modified, less aggressive nonlinear periodization is what I use most often.

How to Make Periodization Work for You

Most runners don’t need to understand the intricacies of periodization, nonlinear models, or the mesocycle (but hey, it’s fun to geek out on our sport occasionally!).

Instead, we just need a few principles to make it work for us in the real world.

And it all starts with a properly planned season (or, ahem, macrocycle). When you get the fundamentals like season length, tune-up races, and phases of training right it become a lot more difficult to fail.

Follow these loose rules once the season is sketched out:

- The beginning of the season should be less intense (i.e., have easier workouts) than the end of the season

- Mileage and the distance of the long run should generally build over the course of the season

- The final few weeks of the season should peak in intensity but decrease in mileage

I also summarized these concepts in a new video on our YouTube channel:

These lessons help put these concepts in context and give you more detail on the two different models of periodization.

Get the Season Planner Worksheet

I’ve created a free worksheet to help you set up your own macrocycle with distinct mesocycles.

It includes:

- Example tune-up race scheduling based on the goal race

- Ideal lengths of time for the macrocycle based on the goal race distance

- The best tune-up race distances for 5k – marathon races

- The 3 ingredients to a successful season

I want to make your next race a HUGE personal best.

It all starts with a good plan, so take advantage of this resource!

After all, better planning means faster racing.