Running on coffee (i.e., caffeinated!), can have performance and health benefits for runners, but be sure to get your dosage and timing right.

For most of us, running on coffee is not a hard sell. One of the first things we probably do each morning is get up and start the coffee maker. We gotta get that cup ‘o joe before our morning run (and before work and taking the kids to school).

Coffee is so ubiquitous that over 2 billion cups are consumed every day, runners can buy countless joke t-shirts extolling the need for a pre-run cup, and it’s the most common thing Pam Nisevich Bede, sports RD and author of Sweat, Eat, Repeat, said athletes will “confess” to her: they drink too much coffee.

But is that really a problem?

“Luckily, there’s little to worry about,” she said—and lots to be excited about. “Personally, I’d be lost without my coffee.”

It’s a good thing that decades worth of research have shown running on coffee has very clear performance perks, not to mention potential health benefits, as long as you don’t overdo it.

Does Coffee and Running Mix?

Coffee is recommended pre-race to help you finish faster!

First studied in the 1970s, the effects of caffeine on running have been poured over by hundreds of researchers for multiple decades. That makes it pretty easy to say at this point: caffeine is definitely an athletic performance booster.

In fact, the World Anti-Doping Agency banned its use from 1984 to 2004—because it was so clearly considered a performance enhancing drug. And, yes, all misconceptions aside, it is a drug.

“It’s a naturally occurring drug,” said Mark Tarnopolsky, a professor, and head of the neuromuscular division at McMaster University. It’s an amazing naturally occurring drug that Mother Nature saw to put all these great things into, he joked.

Performance benefits of coffee

Multiple scientific reviews of the research done on athletic performance and caffeine have found numerous benefits of running on coffee. “Caffeine is one of the most well researched, proven, and widely accepted ergogenic aids available to athletes,” said Bede.

While there’s some evidence of it boosting speed and sprint performance at 30-second high-intensity activity, the predominant benefits seem to come for longer duration endurance activities, where caffeine regularly boosts time to fatigue and decreases perception of effort.

Here are just a few of the things that have been found to improve with the help of caffeine:

- It improves time to muscle fatigue, and increases muscular strength and power.

- And reduces perceptions of pain and effort.

- Improves reaction time, focus, and can have significant impact on mood and anxiety at low doses. (At high doses, which we get to below, caffeine can increase anxiety.)

- In one study, running on caffeine decreased the time for a 1500m on treadmill, increased the speed of a finishing burst in that 1500m, and increased VO2max.

- Studies have shown increased performance in a 5K time trial, 1-mile runs, and on cycling time trial performance.

- One study even found that pre-workout caffeine consumption reduced post-workout muscle soreness.

Overall, said Aj Ali, professor of sport and exercise science at Massey University in New Zealand, who conducted a systemic review, there’s been found to be on average a 2.52% improvement in performance from caffeine.

Health benefits of coffee

While most studies on performance benefits have been done on caffeine (i.e., the chemical itself, typically via pill form), not specifically on running and coffee, there are also a number of known measurable health benefits linked directly to coffee. Regular coffee consumption has been linked to everything from decreased risk of Type 2 diabetes to decreased risk of Parkinson’s to improvement in brain health and providing a protective factor against dementia and Alzheimer’s.

“I want to be healthy, and this stuff [coffee] has all sorts of antioxidants and all kinds of great stuff that Mother Nature somehow knew and put in there,” said Tarnopolsky. That’s one of the reasons he’s a big fan of coffee as opposed to caffeine pills or energy drinks. “There are about 1,000 different molecules in [coffee], all of those things have been shown to be beneficial.”

Of course, as with nearly everything, too much of a good thing can be a bad thing—even running and coffee.

How Does Caffeine Work?

This is actually a more complicated question than you’d think. While we all know that a cup of coffee can give us that extra little boost when we’re falling asleep in the afternoon or if we want a little more focus to finish that big project, how exactly it provides that benefit when running on coffee is still a subject of debate.

“It’s a bit of a chicken and egg,” said Tarnopolsky—by which he means it’s hard to say if it’s your brain or your muscles. Can you push harder because your muscles aren’t fatiguing as quickly? Or does it just feel like your muscles are stronger because your brain lets you push harder? Turns out it’s kind of both. “It works directly at the level of the muscle and at the level of the brain,” he said.

Your cup of coffee is quickly absorbed through your GI tract and appears in your bloodstream, with elevated caffeine levels at just 15 minutes post-consumption and peaking close to an hour (depending on factors mentioned below). It’s long been believed that caffeine blocks the receptors that detect adenosine, a molecule that builds up with fatigue in your brain.

But another study Tarnopolsky and colleagues conducted attempted to shock the muscles directly and found that as they fatigued coffee enhanced the release of calcium, which regulates muscle contraction. As muscles fatigued and muscle contraction weakened, caffeine and the calcium release lessened the muscle weakening.

A new study also confirms that it may be both: Muscles directly stimulated in a cycling to exhaustion test seemed to fatigue less and the brain signals weakened less on caffeine. They also found blood oxygen levels remained higher in the caffeinated athletes.

Running on Coffee: Dosing

What is that optimal dose then? If coffee is great for running, but too much can cause issues, what’s the right amount of caffeine?

“The best dosage is typically within the range of 3-5 mg/kg of bodyweight, but the best timing of intake can vary according to the event and individual,” said Louise Burke, a researcher and the former head of sports nutrition at the Australian Institute of Sport.

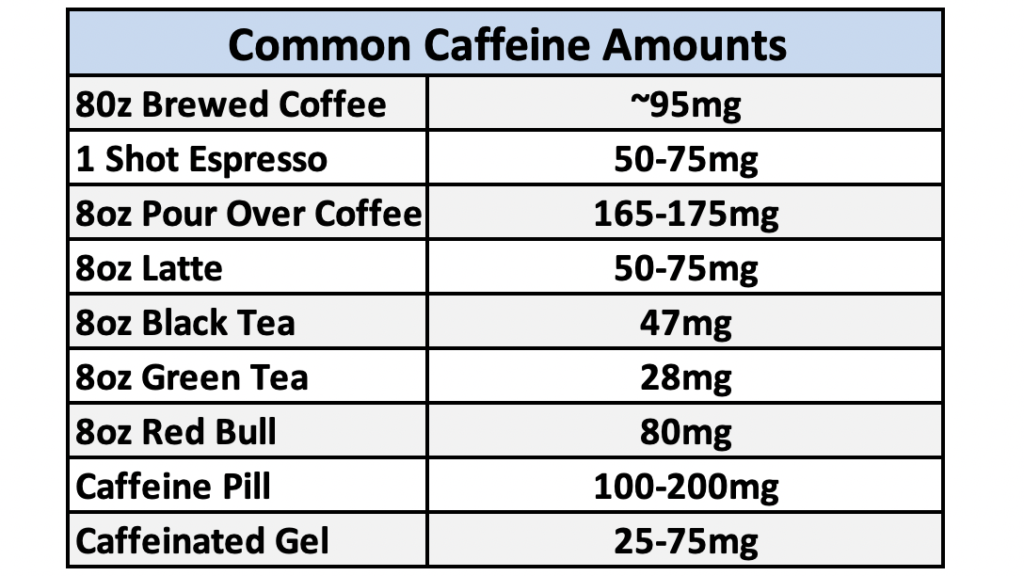

Most studies have found all of the above-mentioned coffee benefits in the range of 3-6mg of caffeine per kilogram of bodyweight. That means, for example, a 130lb. runner (approx. 59kg) should aim for 177-354mg of caffeine—and most researchers agree that, because of the potential for side effects at high doses, it’s better to err on the lower side of that range.

Burke has even found that very small amounts of just 25mg taken later in longer races can produce similar performance benefits. Think of the cup of Coke you grab in the second half of a marathon or Ironman.

What does that mean for your morning pre-run coffee? Essentially, one strong cup (12 ounces) of coffee 45 minutes to an hour before you start is probably the ideal amount for performance, depending on your size and metabolism.

There are, of course, some “non-responders.” According to Ali, up to even 33% of the population won’t see the full benefits and may need to test efficacy to find optimal levels.

Common caffeine amounts:

How much coffee is too much?

While running on coffee is no longer banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency, there are still some specific rules regulating uber high caffeine amounts.

For instance, the NCAA caps urinary caffeine levels at 15 mg/mL (which amounts to about 500mg total, depending on your size—an amount that would also be counterproductive and hurt your performance anyway). The FDA recommends a daily average cap of 400mg.

Many athletes will start to see decreases in performance above the optimal 3-6mg/kg of bodyweight—and some will see decreases in performance and trouble sleeping even at 300-400mg of caffeine (Think of how you feel after that third cup of coffee in a row!). And at 1,000mg total, health consequences beyond running performance start to come into play, including heart palpitations.

“If a little bit is good, more is not better,” said Tarnopolsky.

When Should You Drink Coffee?

As anyone who’s downed a cup of coffee will know, that caffeine can hit you pretty quickly. The half-life of caffeine is about 5.5 hours—though older people have a slower caffeine metabolism, said Ali, and the menstrual cycle can also affect caffeine metabolism. Birth control is known to slow the caffeine half-life.

The method of intake also matters. Caffeine gum will be processed faster, for instance, and warm drinks can also impact the time to digest.

To hit the optimal benefits of running on coffee, you should likely take the 3-6mg/kg about 45 minutes to one hour before your start line—allowing caffeine levels to peak during your race before they eventually start to clear around six hours. (For sprint or strength events, Ali said optimal timing would be more like three hours before.)

During the run

While you probably can’t drink coffee during your run (unless it’s an ultra), you can continue to hit small amounts of caffeine throughout. “This offers some practical advantages of not adding caffeine to the pre-race/game nerves that many athletes feel, and also of allowing the athlete to time the caffeine hit to counteract the onset of fatigue during the session,” said Burke.

Once you start with that mid-race Coke, the general rule is to continue to do so because exercise accelerates the use and clearing of caffeine.

Post-run

While not all of us are hitting Starbucks after our runs, we could. Caffeine consumed with carbs has been shown to increase rates of muscle glycogen resynthesis.

Should you cut out coffee leading up to a race?

A common subsidiary question—especially for the daily coffee drinkers! —is if you need to cut out the habit leading into a race to get the benefit.

Logically, that kind of makes sense, but scientifically it doesn’t seem to be necessary. In one study, cyclists improved their time trial performance after caffeine both whether or not they had abstained for the four days leading in.

Other studies have suggested that while there may be some perks after abstaining for 12-48 hours, those may be more of a result of alleviating withdrawal symptoms than enhancing performance.

Certainly, heading into a key workout or race isn’t a time to overdo it on the coffee. But if you’re tapering, then going into extreme caffeine withdrawal might instead just add to the unpleasantness.

Coffee & Running Performance: Things to Watch Out For

Of course, there are some common concerns that come up when using caffeine—whether running on coffee, caffeinated gels, or caffeine pills. Fortunately, some of those concerns have been shown not to be an issue or have been misunderstood.

Dehydration: A common complaint is that coffee can dehydrate you—something no athlete wants. And it is true that when you first take it it can act as a diuretic because of the dilation of the renal artery, but for habitual users that increased urination usually stops after three or four days, said Tarnoposky. If athletes are experiencing issues with dehydration during races, “they’re usually just not drinking enough,” he said.

GI issues: Another common issue: the port-a-potty stop. In fact, many runners have that pre-run cup of coffee precisely because they think it’ll “prime the pump” and clear out the pipes before they get going. Of course, the reality is you can prime the pump with lots of non-caffeinated things too. (Trust me.) In research, GI issues have not been shown to be correlated to caffeine, except at excessively high dosages, and can often be complicated by all the other things runners take during a race.

Heat: One effect of caffeine is that it does increase your heart rate and blood pressure. Whether this has an impact on thermoregulation when running in the heat is less clear in the science. It’s hard to distinguish between the direct effects of caffeine and the indirect effects of it allowing you to work harder, said Burke. And, making sure you’re hydrating and fueling correctly also become more important in the heat.

This, however, is all at optimal dosages. At high doses, caffeine can lead to headaches, jitteriness (which is particularly a problem pre-race), and trouble sleeping (also never good for recovery). Doses over 1000mg or chronic overuse can even cause heart palpitations.

While some studies have found more of a performance benefit in caffeine pills over coffee, “I’m a big fan of coffee as opposed to caffeine,” said Tarnoposky. It lets you self-regulate—i.e., it’s easy to overdo it and lose track with caffeinated sports products, as opposed to simply pacing and drinking your regular coffee—and it lets you get in fluids and enjoy the additional natural benefits of all those coffee beans.

Really what isn’t there to love about coffee and running? They go together like hill sprints and strength work!

Try Strength Running’s Electrolyte-Infused Coffee!

Because we recognize the performance and health benefits of coffee for runners, we’re excited for you to try our new electrolyte-infused coffee!

In partnership with Long Run Coffee, we’ve created coffee made specifically for runners.

The Strength Running Roast is electrolyte-infused coffee that can be ordered as light, medium, or dark roast (and code SR10 will save you 10%).

It’s designed for performance:

- Infused with essential electrolytes

- Premium coffee freshly ground before shipping

- Free of sugar, additives, flavorings, and dyes

Ever since I used to drink a bottle filled with cold, black coffee before track races in college, I’ve been hooked on running on coffee. It’s my pre-race (or workout) ritual.

If you haven’t had a good cup of coffee before a race, it’s time to get wild.

Order your bag here (use code SR10 to save 10%), enjoy, and let’s race faster!

***

This article was written by Kelly O’Mara. She is the former editor-in-chief of Triathlete Magazine and writes the Triathlonish newsletter.