Isn’t it funny that some people KNOW what to do with their running – when they’re actually totally wrong?

Some runners think sprinting 200’s is a great workout for the marathon. [More bad marathon advice]

Or that they got runner’s knee because of cutting their warm-up routine short.

There’s a lot of misconceptions in the running world (but not by Strength Running readers – you’re all geniuses) and today I want to shatter a few crazy myths that I’ve heard recently.

Obviously, I don’t know everything about running. Nobody does and you should run for the hills if anyone claims that they know it all. The beautiful aspect of running and coaching is that you’re always learning new ways to train more effectively.

But I’m a USA Track & Field certified coach with over 14 years of running experience. I ran in high school, college, and beyond and have raced everything from the 200m to the marathon (with a 2:39:32 personal best). I’ve been fortunate to have learned from about 10 coaches over my 8 years in organized cross country and track and field.

So when I hear someone say something wacky about running, I want to set the record straight so you don’t make the same mistakes.

You should do your own research and find reliable sources of training information that you trust. Use that to better inform your running so you can train smarter, run easier, and ultimately race faster.

That’s my goal with Strength Running. And that’s why I want to dispel three misconceptions I’ve heard floating around the web.

“My last injury was a bad case of DOMS”

DOMS – or Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness – is muscle soreness that occurs 1-2 days after a hard workout. It’s not specific to running and can happen after any tough session, like weight lifting or cycling.

But DOMS is not an injury. In fact, a healthy dose of soreness after a long run or particularly challenging fast workout is a normal and welcomed part of the training process.

I think that last part is critical so I’ll repeat it: some DOMS is a welcomed part of training!

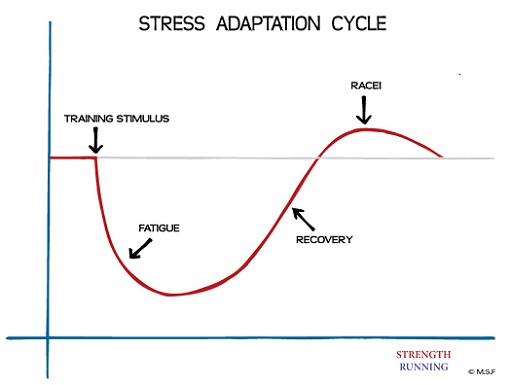

See, soreness is just your body’s way of telling you that you pushed yourself out of your comfort zone and inflicted some damage to your muscles. That’s a good thing because without some minor damage, there would be no adaptation.

Adaptation occurs when you recover from that damage and your body supercompensates – then you get faster. Let’s go back to my favorite training graph, the Stress-Adaptation Principle:

Of course, balancing smart training with over-training is critical here. If you fatigue yourself with a workout too challenging than what you’re ready to run, you might:

- Experience an overuse injury

- Compromise your next important workout

- Need a reduction in training to recover properly

They key is to avoid the “three too’s” of poor training: doing too much, too soon, too fast. Instead, follow the principle of progression and do workouts that are appropriate to your fitness level and training goals. You’ll reduce excess soreness but experience the right amount to keep improving.

“My 10k PR is 49:00 but I’m hoping to get to 30-35 in the next two years.”

I love runners who set stretch goals and believe they can run faster. That’s one of the universal traits of runners – we always think we can go a little faster.

Big goals should always be paired with smaller goals (or “small wins” as I like to call them) that help you stay motivated as you inch toward your stretch goal. That’s what helped Matt run nearly two hours faster in the marathon to eventually qualify for Boston.

But being realistic is important. It keeps you from being disappointed in a performance that you should otherwise be proud of.

I know that I’ll never run a sub-4 mile. With a 4:33 PR (after 8 years of training) I’ve come pretty close to what my body is capable of doing in the mile. And with a 2:39:32 marathon PR (after 13 years of training) I’ll never run an Olympic Trials “A” Qualifying time of sub-2:19. It’s just not physiologically possible.

And that’s ok – it allows me to focus on realistic stretch goals like someday running 2:30 in the marathon.

But what does a 14-19 minute improvement look like in a 10k race?

A 49:00 10k time is 7:54 per mile. A 30:00 10k time is 4:50 per mile.

Those times are in different universes. If this person can run one 4:50 mile, they should be able to run much faster than 49:00.

While seemingly impossible goals are fun and a huge source of motivation, they should still be in or close to the realm of possible.

I also should point out that this runner was a woman. A 30:00 time would put her as the sixth fastest female 10k runner of all time!

So instead of setting yourself up for disappointment, it’s smarter to set incremental goals with the final goal being your “stretch goal.” For this runner, it might be:

- break 45 minutes in 6 months

- break 40 minutes within 18 months

Just remember – the faster you get, the harder it is to set new personal bests.

“I’m not going to fuel during the marathon and hope adrenaline will get me to the finish line.”

Yikes. Where do I begin?

First, adrenaline is not a long-term fuel. It’s meant to temporarily increase your strength or speed so you can run away from a lion or lift a boulder off your mate. That’s how it evolved. But it won’t help you after 3+ hours of (relatively) low intensity activity.

Running 26.2 miles is a test of your aerobic fitness, structural ability to withstand hours of impact, and fueling. If you master those three variables then you’ll run fast and feel good. Or, as good as you can feel during a fast marathon.

Let’s focus on fueling. Very slow runners may get away with eating no carbs during a marathon even though they would probably feel better with eating some carbohydrates during the race.

But if your goal is to run a PR in the marathon or hit a certain goal time, you need to plan your carb-loading just as carefully as your long run progression. Maxing out your glycogen stores (the sugar available in your muscles) is vital to fueling a fast marathon.

The majority of this fueling should be done during the 24-36 hours before the race. But in-race fueling can help you stay fueled during the final several miles of a marathon when you’re depleting the amount of sugar that your body can store in its muscles and blood stream.

In an interesting study, runners who rinsed with a sports drink altered their brain’s perception of fatigue. It seems that simply rinsing your mouth with a sports drink is enough to trick your brain into thinking there’s more fuel available because of carbohydrate receptors in the mouth.

If you’re a runner who wants to improve your marathon, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that carb-loading is overrated. You could throw away months of good training and run a poor race if you don’t take race nutrition seriously.

Question for you: What “myth” or misconception about running have you heard lately? How did you find out it wasn’t true?